Squire Osbaldeston (left) and William Lambert. Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons (Osbaldeston), The Hambledon Men by John Nyren (Lambert)

7 July 1810. A double-wicket match was scheduled at Lord‘s , with Lord Frederick Beauclerk and Thomas Howard on one side, and William Lambert and Squire (George) Osbaldeston on the other. Just before the match, however, Osbaldeston fell ill and wanted to have the match called off. Unfortunately, Beauclerk was in no mood to relent, so Lambert had to play almost entirely on his own. He ended up winning it. Abhishek Mukherjee looks back at one of the greatest single-handed efforts in the history of the sport.

Before narrating the tale, let me provide an introduction to single-wicket cricket. In the early days of cricket, when England was not connected by railways, it was often logistically difficult for organisers to arrange for 11-on-11 matches. Single-wicket matches were, as a result, in vogue.

The most significant of these was played in 1775, when the two legends Lumpy Stevens beat John Small thrice in a row. Every time the ball passed between the two stumps, Small was given not out, for that was the rule of the sport at that time. As a result they decided to introduce the middle stump.

The format became extremely popular in the early 19th century, and was often played for cash. Fixing matches were not unheard of and huge amounts were put on stake.

Thus, when Lord Frederick Beauclerk and George Squire Osbaldeston two leading amateurs of the era were set to clash in a single-wicket contest at Lord s, which naturally attracted enormous public interest. The two-man teams played for a prize money of fifty guineas, but the audience played for thousands more.

Note: For the uninitiated, 1 guinea was approximately 1.05.

To make the clash even more spectacular, the amateurs hired the services of one professional each. While Osbaldeston opted for all-rounder William Lambert, Beauclerk acquired the services of Thomas Howard.

This made it technically a double-wicket contest; though it is, for some reason, recorded as a single-wicket match. The rules, however, were similar to a single-wicket match: batsmen would bat one at a time, and a side would need to take two wickets (as opposed to usual double-wicket matches, where one wicket used to suffice).

Before getting into the details of the contest, let me introduce the four men.

Osbaldeston

If we go by contemporaries, Osbaldeston was one of the fastest bowlers of the era (if not the fastest). If one goes by his own words, sometimes when I bowled a man out, the bails were found fifteen or sixteen yards from the stumps . Even if we allow some exaggeration, that is a lot.

But there was more to the man than that. The son of a Scarborough MP, Osbaldeston went on to become an MP himself, for West Retford, and later, High Sheriff of Yorkshire.

Amidst all this, he was expelled from Eton (and almost from Oxford); he was a prolific horse-racer, carriage-racer, steeplechaser and billiards player. He was a crack-shot who once shot 98 pheasants in 100 attempts (as per CA Wheeler). He was also one of the most renowned fox-hunters, and once sent a bullet through Lord George Bentinck s hat in a duel. A womaniser of the highest order, his range varied from his mother s friends to his friend s daughters.

An instinctive gambler, Osbaldeston later ran into debts, and was forced to sell his land once the amount exceeded 200,000. He died almost penniless.

But let us focus on his cricket days. He played 33 First-Class matches, scoring 1,002 runs at 19 in an era when 25 was considered a big innings. He also claimed 45 wickets. However, he was noted for his prowess in single-wicket cricket (which mostly remain undocumented), for which he travelled extensively along the country.

Beauclerk

Son of the 5th Duke of St Albans, Lord Beauclerk was not as versatile as Squire Osbaldeston. He excelled in only one sport, but was seriously good at that. He scored 170 for Homerton against Montpelier in 1806, at that point the highest score in any form of cricket. His 129 First-Class matches fetched 5,442 runs at 25 and 349 wickets, which tells a thing or two about his prowess.

His batting was as correct and orthodox as the professionals of his era, while his accurate under-arm bowling often kicked from a length. He was also a first-rate slip fielder. Clad in white shirt, nankeen breeches, a scarlet sash, white stockings and a white beaver hat, he was a sight to behold on the cricket field.

Despite being a cricketer of such calibre, Beauclerk earned notoriety during his era as MCC administrator. An unqualified eulogy of Beauclerk has never been seen and that is significant, wrote Rowland Bowen, who went to the extent of calling him an unmitigated scoundrel .

Jonathan Rice wrote that he was “a foul-mouthed, dishonest man who was one of the most hated figures in society … he bought and sold matches as though they were lots at an auction. If one were to believe rumours, an infamous convict once refused to share a train compartment with him. Even The Times did not run an obituary for him.

What was Beauclerk like? Tony Lewis wrote: In the absence of a full-time secretary of the Marylebone Club, he pronounced to all on the Laws and their spirit. For someone who had established himself as the custodian of the laws, Beauclerk was as prolific a better as Osbaldeston, and went to the extent of bribing a scorer to win a bet.

To summarise, he was an autocrat, a despot, a match-fixer and a cheat. It is estimated that he earned about 600 a year from cricket, mostly by placing bets on matches.

A Doctor of Divinity, he later became Vicar of St Michael s Church, St Albans. Of his new role, Bowen wrote that he was a cleric without, it would seem, the faintest interest in being a clergyman or any kind of Christian. If that was not enough, Derek Birley, in A Social History of English Cricket, mentioned that he was completely devoid of Christian charity.

Lambert

Lambert and Howard, of course, did not hail from aristocratic backgrounds. The son of a shepherd, Lambert went on to become the most accurate and vicious bowler of the era. In The Hambledon Men, John Nyren wrote: His perfection is accounted for by the circumstance that when he was tending his father’s sheep, he set up a hurdle or two and bowl away for hours together.

Probably a better batsman than bowler, Lambert scored 107* and 157 for Sussex against Epsom in 1817, the first instance of a batsman scoring two hundreds in a First-Class match. Bizarrely, this turned out to be his last First-Class match, for he was banned for life for fixing a match.

Lambert scored 3,014 runs from 64 matches at 28 and claimed 187 wickets. He was also an outstanding fielder and a quality wicketkeeper (he had 87 dismissals). Lambert s all-round prowess made him one of the finest single-wicket cricketers of the era. In Scores & Biographies (Volume 1) Arthur Haygarth called him one of the most successful cricketers that has ever yet appeared, excelling as he did in batting, bowling, fielding, keeping wicket and also single wicket playing.

Howard

Howard, the fourth and least glamorous of the quartet, bowled very fast underarm. Just like Lambert, he also kept wickets and was a competent batsman. His 88 First-Class matches fetched 1,539 runs at 11, but 326 wickets and 137 dismissals (on field and as wicketkeeper) more than made up for it.

Prelude

But let us get back to our match. Osbaldeston fell ill on the morning of the match, on July 6. He sent his friend Edward Hayward EH Budd to approach Beauclerk, requesting him to postpone or cancel the contest.

But Beauclerk would have none of it. The response was prompt: Play or pay.

Budd carried the news to Osbaldeston, who was in no condition to play. However, his ego did not allow him to concede: I won t forfeit; Lambert may beat them both; and, if he does, the fifty guineas shall be his.

James Pycroft (author of The Cricket Field, one of the earliest and most comprehensive cricket books) later recollected that Osbaldeston was more than confident about Lambert defeating both Beauclerk and Howard single-handedly.

Whatever Beauclerk was expecting, it was not this: Nonsense! You can t mean it!

It was now Osbaldeston s turn to get back: Yes; play or pay, My Lord; we are in earnest, and shall claim the stakes.

The match

So the match began. Osbaldeston asked for a substitute fielder, but Beauclerk refused point-blank (after all, fifty guineas and a lot of pride were at stake!). But Osbaldeston did show up in a carriage, accompanied by his mother. By the time he reached, Lambert had been bowled by Howard for 56.

Osbaldeston recalled in his autobiography: I went in; but from the quantity of medicine I had taken and being shockingly weak from long confinement to my room, I felt quite dizzy and faint. Lord Frederick bowled to me. Luckily he was a slow bowler, and I could manage to get out of harm s way if necessary, but it did not so happen. I hit one of his balls so hard I had time to walk a run.

Osbaldeston retired immediately after that run. The score read 57.

Now Lambert took field alone amidst a lot of cheering. Pycroft wrote: Of course, all hearts were with Lambert, and his adversaries must have felt their spirits rather damped on the occasion.

Beauclerk went in first and to his credit scored 21. Then Lambert did something brilliant: he bowled a slower delivery and followed it along the length of the pitch; Beauclerk simply stroked it back, but before the shot hit the ground, Lambert had reached it.

Beauclerk was not amused. Silver Billy Beldham, the champion cricketer of the era who was present at the ground, described his reaction: Lord Frederick was caught so near the bat that he lost his temper, and said it was not fair play.

But he had to leave. Three runs later, Lambert bowled Howard, securing a 33-run lead. He scored 24 in the second innings before Howard bowled him. Osbaldeston did not bat, and Beauclerk s men were set 58.

One must remember that Lambert was bowling on his own, without a fielder. Barring those three balls faced by Osbaldeston, he had batted or bowled throughout the match. By the time he took field for the fourth time he had already faced 281 balls and faced another 60, without a break.

Restricting both Beauclerk and Howard was a big task, but doing it single-handedly without a fielder for the second time in a match was nigh-impossible. Nevertheless, the lion-hearted Lambert refused to give up.

By the time an exhausted Lambert bowled Howard, the latter had already batted 106 balls for his 24. Beauclerk needed another 35, but how long could Lambert sustain? Of course, the match had already moved to its second day…

He devised a new plan, and started bowling well wide of the stumps. Remember, this was 1810, and wides did not contribute to the total. Beauclerk got his bat to a few, but they were generally beyond his reach. This added to the frustration of His Lordship.

Pycroft wrote: Lambert bowled wides purposely to Lord F. Beauclerk in order to put him out of temper in which he succeeded. Simon Rae wrote in It s Not Cricket: He started bowling wider and wider outside the off-stump, until his lordship once again lost his temper, and then finally presented with a straight ball, attempting to vent his pent-up anger at it.

Lambert hit timber. Beauclerk had faced 60 balls, but had scored a mere 18.

An exalted Osbaldeston reminisced in his autobiography: I was never more gratified in my life than I was when Lambert bowled his lordship out and won the match.

Lambert collected his hundred guineas. There was something else waiting for him as well. Beldham wrote: Osbaldeston s mother sat by in her carriage and enjoyed the match; and then, Lambert was called to the carriage, and bore away a paper parcel; some said it was a gold watch some suspected bank-notes. Trust Lambert to keep his own secrets. We were all curious, but no one ever knew.

Indeed, as Pycroft later recalled, Lambert thus actually, alone and unassisted, beat two of the best men in England.

Postscript

The match did not go down well with Beauclerk. His revenge was threefold:

1. The next year, in 1811, he used his authority in MCC to ensure wides would not be considered as legal balls. It turned out to be a revolutionary idea, but the intention behind the thought was certainly not noble. However, it was not until 1827 that a wide would be considered as a run.

2. Remember Lambert’s ban? That was Beauclerk s idea. He accused Lambert of throwing a match between Nottingham XXII and All-England XI a contest where, according to Martin Williamson of ESPNCricinfo, both sides had taken money to lose . Given that fixing matches were common (and accepted, in general), the ban had certainly to do with emotions beyond the spirit of the game.

Note: Interestingly, Beauclerk, Osbaldeston, Lambert, and Howard all played for England XI, who lost the match by 30 runs. Lambert claimed 8 wickets in the match and Beauclerk 3. With bat, Lambert scored 7 and 9, while Beauclerk managed 8* and 3. Lambert also had 4 catches and a stumping to his name. It really does not seem likely that Lambert was playing against his side.

3. Osbaldeston lost a match against Sussex s George Brown a year after Lambert s ban. He lost his temper at this, and quit as MCC member. He reapplied once he realised his error. He had obviously underestimated Beauclerk and his ability to hold a grudge.

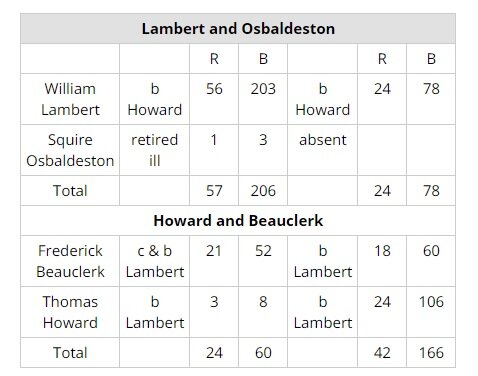

Scorecard:

Lambert and Osbaldeston won by 15 runs.