Arunabha Sengupta looks at some of the most famous feuds of cricket. In this episode he looks at some of the bitter conflicts in the history of Pakistan cricket.

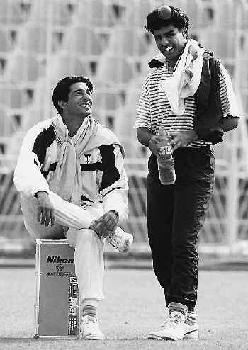

Imran and Miandad

One oozed charisma, Oxford chiselled sophistication and a pride in his ability that often got interpreted as arrogance.The other was crafty, street smart, with a crude penchant for getting under the skin of opponents. Both were icons, two of the greatest cricketers produced by Pakistan.

In 1982, Javed Miandad was one of Wisden’s Five Cricketers of the Year. Imran Khan emulated him the following year.

And while Imran is remembered for his magnetic leadership which culminated in the World Cup win of 1992, Miandad was often the tactician in the background, who was in fact a more successful captain in Test cricket.

And while they did come together and combine for the cause of the country, often acrid fumes of bitterness did cloud their relationship. Even today it is difficult to extract mutual praise without persisting undercurrents of resentment.

While the traditional Lahore-Karachi tensions have often been attributed to the sparks that flew between the two, the real reason perhaps is the equally time-tested problems of social class. It was perhaps Pakistan’s own version of the English curiosity of Gentlemen vs Players. With Imran being endowed with too much and Miandad with too little of accepted social status, both found it difficult to gel within the team and with each other.

Miandad still bristles when he remembers Imran declaring the innings at Hyderabad (Pakistan) when he was batting on 280, looking good to overhaul the world record of 365 by Gary Sobers against a friendly Indian attack on a featherbed of a wicket.

“Off the field at the end of the second day, there was no talk of a declaration. Imran never brought it up overnight and gave me no specific instructions. I took this to mean I was being given a chance to go for all possible records. How wrong I was!” – writes Miandad in Cutting Edge My Autobiography.

He also accuses Imran of plotting against his captaincy in 1993. “I don’t know what Imran’s motives were, I can only guess them. Perhaps he felt an undisturbed Miandad captaincy would overshadow his legacy,” he writes. He also claimed that during a tour to England, Imran threw a party for the team to which he and two other senior players, Saleem Malik and Rameez Raja, were not invited.

Imran is also largely credited to be the instigator of the rebellion against Miandad’s initial spell of captaincy in 1981.

The all-rounder’s own grievances are more subjective. They hint at Miandad’s scheming mind, regular face-offs with one and all, and his political games in the dressing room.

When Pakistan lost to India in the World Cup group match in 1992, with Miandad scoring 40 off 110 balls, Imran went public saying that some senior batsmen had batted way too slowly.

However, the two worked together splendidly as well. It was generally accepted that the two often acted as simultaneous leaders, Miandad coming up with strategies and Imran passing on the command to the rank and file.

There is a story about the 1992 World Cup which underlines how much they depended on each other, in spite of their differences. After Pakistan had lost a group encounter against South Africa, due more to the rain rule than performance, Imran had stormed off and flung his bat across the dressing room. When photojournalist Iqbal Munir approached the room, attempting to take a picture, Wasim Akram stopped him, saying, “Where do you think you’re going? The only person who can approach Imran right now is Javed.”

It did bear fruit, since a few days later, joining hands at 24 for two, the two of them added 139 in the final and set up the platform for the World Cup triumph.

Sarfraz Nawaz and Asif Iqbal just did not gel

When Asif Iqbal led the Pakistan team to India in 1979-80, Sarfraz Nawaz was left out of the squad. It was surprising to say the least, because Sarfraz, at that point, was the leading speedster of Pakistan. According to the pioneering fast bowler of the country, Fazal Mahmood, Sarfraz was quicker than he himself had been and had more variations. He had already been playing Tests for a decade and was more experienced than the redoubtable Imran Khan.

When the team lost the series 0-2, uncomfortable questions were asked about his omission. It was a well-known secret in the Pakistan cricket circles that the mild-mannered skipper and the controversial fast bowler did not get along too well.

Much later, Asif accepted that although he had immense respect for Sarfraz’s ability, he did not feel he could have handled the temperamental paceman prone to mood swings, confrontations and idiosyncrasies.

Sarfraz, on his part, was not very forgiving. In a statement made in 1998, he openly hinted that the ex-Pakistan captain was one of the first players to be involved in match-fixing. He voiced suspicions about the toss and surprise declaration during the Eden Test of 1979-80 and also stated that during the tour Asif shared rooms with Raj Bagri, the biggest bookmaker in India.

Mike Gatting is lucky I didn’t beat him: Umpire Shakoor Rana

In 1978, when India resumed cricketing ties with Pakistan after 17 years, Shakoor Rana, the officiating umpire, warned Mohinder Amarnath for running on to the danger area during his follow through. An incensed Sunil Gavaskar, the vice-captain of the side, walked up to Rana and charged him with allowing Imran and Sarfraz to overstep while they bowled at the Indian batsmen. While the issue was resolved diplomatically given the high profile political implications of the tour, it was Rana’s first major brush with the touring cricketers.

In December 1984 during the Test in Karachi, the normally cheerful New Zealand captain Jeremy Coney threatened to take his side off the field after an appeal against Javed Miandad was turned down by the same umpire.

Speaking from the commentary box years later, Ravi Shastri recalled his first tour of Pakistan in 1982-83. “Imran and Sarfraz would make the ball swing, and then there were those two umpires, Khizer Hayat and Shakoor Rana. It was like playing a four-pronged pace attack.”

Unfortunately, the same two umpires were officiating in the second Test between Pakistan and England in Faisalabad, December 1987. Rana had already earned the wrath of the English captain Mike Gatting during the previous Test at Lahore by putting on a Pakistan sweater.

With three balls to go on the second day, and Pakistan struggling at 106 for five and Eddie Hemmings bowling, Gatting brought David Capel in from deep square-leg to prevent a single. According to him, he had informed the batsman Saleem Malik, but Rana, standing at square leg, stopped play and accused him of cheating.

A furious Gatting confronted the equally riled umpire, both wagging their fingers threateningly and exchanging a spate of swear words, a lot of it heard worldwide, transmitted through the stump microphone.

A furious Rana refused to continue to officiate unless an apology was rendered and Gatting steadfastly refused to oblige him. “In Pakistan many men have been killed for the sort of insults he threw at me. He’s lucky I didn’t beat him,” Rana said after the row. Gatting claimed that the square-leg umpire had no business getting involved in the game and he himself had no reason to apologise.

A day’s play was lost, Foreign Office got involved and the British Ambassador was called in to soothe the Anglo-Pakistan relations. Gatting, threatened with the loss of English captaincy, was forced into writing an apology. “Mike Gatting was packed off to the headmaster’s study without so much as a Wisden to stick down the back of his trousers,” wrote Martin Johnson in The Independent.

The Pakistan board stood solidly behind Rana, appointing him as umpire for the deciding Test. The decision was revised only when it became clear that England would not play if Rana officiated. Test and County Cricket Board (TCCB) subsequently paid all players in the England squad £1000 as ‘hardship’ bonus for the tour.

A legend has grown that Rana used to keep Gatting’s brief scrawled apology under his pillow. He later went on record saying, “I do not regret what happened. How can I regret? It made me the most famous umpire.”

Rana stood in just three more Tests. However, he remained at peace and happy about his 15 minutes of fame, often charging considerable sums for interviews about the incident. He also told and retold the story of the pair meeting again in England years later. Gatting had supposedly exclaimed, ‘Oh God, not you again,’ and driven away.

Gatting was sacked as captain six months later for a supposed incident revolving around a bar maid in his hotel room during a Test match (Amul captured this in an ad: If life’s Gatting bad, have a ball with Amul Butter. You can even take it to your room.) However, many still link his sacking with the Rana incident.

Gatting later admitted that “It wasn’t a very proud moment of my career. It is one of those things that has gone down in history. It will probably always be remembered.” However, there is a section of cricketing fraternity who feel that he should have apologised for writing that apology to the pompous Rana.

The incident was probably the catalyst that hastened in the age of neutral umpires.

When Inzamam was the messenger between warring Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis

One could make the ball swing as if by magic, and the other could send down yorkers at will. The two formed the most feared of all opening bowling combinations in the ’90s. Yet, things were never very smooth between the two.

Wasim Akram has gone on record stating that although he hated Waqar to the extent that they did not speak to each other, it was a professional rivalry which spurred them on to perform better. “Every time Waqar took wickets, I too would too get charged up to do the same.”

However, according to many, which include Mudassar Nazar, the infighting had dreadful results for the Pakistan side. Mudassar accused the board officials of turning a blind eye to the rivalry, and often encouraging it in order to maintain their own positions of power.

Things reached a severe crisis during the 2003 World Cup in South Africa when the two speedsters could speak to each other only through Inzamam-ul-Haq, probably the only player on speaking terms with both the great bowlers.

When Waqar was named the captain of Pakistan, at least half the side pledged allegiance to Akram. The dynamics within the team grew extremely complicated. When Akram wanted a change in the field, he would shout the instructions to Inzamam in the slips, who in turn would pass the message to Waqar. Shahid Afridi, while bowling during the match against India, chose to complain to Akram when he was not given the field of his choice and then fired his deliveries down the leg with a packed off side field.

However, with age having mellowed them down, the two fiery fast bowlers claim to be on good terms now that they have retired from cricket.